fortnite account with black knight

Brian Esperon started dancing with a local dance studio as an 8-year-old growing up in Guam. It wasn’t until he returned home from college years later that videos of his performances with the company began to go viral.

In 2020, Esperon created a dance for “WAP,” the popular song from Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion. His dance was such a hit on the short-form video platform TikTok that Cardi B tweeted out a clip of Esperon’s performance the day after it was released. But even the singer’s shoutout wasn’t enough to ensure Esperon received the same level of recognition as the dance he created.

It didn’t take long for his video to be eclipsed by others using his choreography, he said, pointing to search results showing the most-viewed “WAP” videos. “The whole top 20 was just like a bunch of like either White girls dancing or dancing with their mom or dancing in front of their parents,” he said.

In the end, Esperon’s original video drew 99.8 million views. But when Addison Rae, a popular white content creator on TikTok, posted a video showing her performing his dance, she more than tripled that total, with 311.5 million views.

Choreographer Brian Esperon

Getty Images

The social media explosion that offers artists a potential worldwide audience has also stoked new questions and challenges over the rights and rewards of creative content.

Attorneys say they’ve seen an uptick in choreographers turning to copyright law in a bid to protect their creations amid a lack of crediting that some assert has been disproportionately acute for creators of color.

Last year, a prominent Black choreographer who has worked with Beyoncé started a company to help other artists, particularly those of color, win credit and copyrights for their dances.

But registration is not guaranteed, and the copyright system hasn’t yet caught up to technology, lawyers say.

“TikTok is kind of a quintessential reason why there needs to be more clarity in the law,” said David Hecht, a New York lawyer who has taken on some of the most notable copyright cases for choreographers.

Decades-old Confusion

Hecht said the current confusion and hurdles for choreographers can be traced to the lack of explicitly clear language and definitions in the Copyright Act, created in 1790. Amendments later added the description “choreographic works” as protected in 1976, but questions remain unsettled.

In the 1986 Second Circuit case Horgan v. Macmillan, Inc., which sought to resolve the question of whether still photographs of a ballet can infringe the copyright on the choreography for the ballet, the appellate court noted that copyright protection for choreography is “an uncharted area of the law.” The chief judge ultimately said that still images did not infringe copyright as the choreography was in the flow of the ballet steps, which could not be reproduced in a photograph.

Under current regulations, improvised choreography is permitted to be copyrighted, whereas simple steps, or “social dances”—meaning dances performed by general members of the public for self-enjoyment, such as swing or folk dancing—cannot be protected.

“With choreography, there’s a lot of things that have to be figured out,” said E. Scott Johnson, an intellectual property attorney in the Baltimore office of Baker Donelson.

Johnson said relevant factors in determining if something is worthy of copyright registration include the duration—down to seconds—of the dance, the originality of the steps, and whether they can be considered “building blocks” for other dances.

“There has to be some parameters,” said Johnson. “If everything can be protected that’s novel, creative or interesting, there would be a chill.”

But there’s minimal guidance when it comes to TikTok dances or choreographed creations intended for social media platforms.

“We’re applying semi-antiquated legal concepts and legal standards to sort of cutting-edge technology and cutting-edge content and how people are consuming content,” said Aaron Swerdlow, an attorney with Weinberg, Gonser Frost LLP in California.

A 2019 Supreme Court decision clarified some of the legal landscape by finding that artists must register their copyrights before suing others for infringement. But registration in itself can be a struggle.

Hecht represented musician 2 Milly and actor Alfonso Riberio in claims against Epic Games, the publisher of the wildly popular Fortnite video game. The artists claimed the game creators used their dance moves the “Milly Rock” and the “Carlton,” respectively, without consent.

Both ultimately dropped their lawsuits because the US Copyright Office had denied them copyright registration. The office ruled the dances were simple steps, not protectable choreographic works.

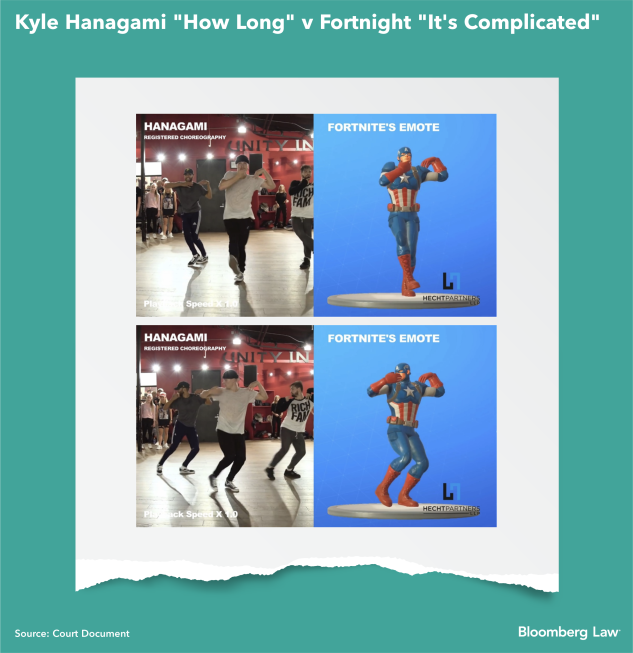

Kyle Hanagami’s lawsuit claimed the creators of Fortnite appropriated his dance.

Hecht is now involved in a similar case that might have more luck. Choreographer Kyle Hanagami sued Fortnite and its creator over an emote—a command or image a game player uses to express a reaction—that he says illegally appropriates a dance he created for Charlie Puth’s song “How Long.” Unlike in the prior cases, Hanagami has successfully copyrighted his dance.

The case is pending.

Attorneys say they’ve noticed an increase in copyright applications by dance creators. But the Copyright Office doesn’t show any clear trends in registration.

Creators of Color Struggle to Claim Credit

Some trace the reckoning over choreographers of color not getting credit for their content to March 2021, when Addison Rae was a guest on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. That night, she performed several viral TikTok dances without crediting the original creators, many of whom are people of color. In response to the backlash, Fallon invited the original creators to his show to perform.

In June 2021, several Black artists on TikTok refused to choreograph dances to a newly released Megan Thee Stallion song as a way of highlighting the importance of Black creators on the platform.

Erick Louis, a 22-year-old content creator and dancer, posted a video to the song with the caption “If y’all do the dance pls tag me,” saying that he didn’t “need nobody stealing/not crediting.” However, there was no dance at all. Instead, Louis raised his middle fingers to the camera and walked away as words appeared on the screen: “Sike. This app would be nothing without Blk people.”

That same year, JaQuel Knight, a Black choreographer who has copyrighted several dances, including his dance for Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies,” created Knight Choreography and Music Publishing Inc. Its purpose: to help choreographers, particularly those of color, copyright and license their creations for commercial use.

Choreographer JaQuel Knight

Getty Images

Knight also proactively reached out to artists he thought could use his help.

One was Keara Wilson, a 21-year-old Black creator from Ohio whose “Savage” dance drew 4.5 million likes on TikTok. She wanted to copyright it, she said, “because of how many people were just taking it and using it on shows and just doing it literally everywhere”—including popular White TikToker Charli D’Amelio, whose own video performing the dance got 8.3 million likes.

But Wilson couldn’t figure out how to navigate the process until Knight and Logitech, a computer gaming equipment company, reached out to help.

Knight also helped brothers Ajani Huff and Davonte House, choreographers from upstate New York who saw their dances used in advertisements on TikTok without getting notice or compensation.

“It was like I was a ghost,” said Huff, who created the “Get Up” and “Red Nose” dance challenges. With a better grasp of their rights and options, he and his brother have since moved to Los Angeles to build on their success.

“Being out of the industry, we had no idea, we were completely oblivious,” said House. “It just took time for us to hang around the right people and now we are aware.”

Community and Platform Protections

Given the murky legal protections, creators on TikTok have relied heavily on other users to hold each other accountable, calling out appropriators who fail to credit original creators.

The platform has also made changes to better accommodate giving credit where it’s due, including having original dance creators’ videos appear first in song search results and launching a tool in May to add a “video tag” linking to a creator’s original work in video captions.

“We know that the impact of diverse creators is invaluable and we are committed to fostering a culture where attribution is the norm by making it easier for creators to give credit to those that cultivate the dances and trends that inspire them,” said a spokesperson for TikTok.

The platform also said it’s taking actions to support creators of color, including starting an account and hashtag to highlight popular content from Black creators and introducing a Black creator incubator program.

Johnson said the fight to give credit where it’s due will take time.

“The case law is going to have to unfold a bit,” he said. “And I think choreographers should meet the moment and register their works.”

Esperon, who struck gold with his “WAP” dance, has mixed opinions when he sees others getting credit for his creation.

“Personally, for me as a dance creator, I’m always just happy when my dance is being shared,” he said. “But when other dancers come up to me and they’re like, ‘Aren’t you a little salty about this?’ Like, I think I am, yeah, now that you mentioned it. I’m definitely missing out on certain opportunities.”

He recalled seeing a TikTok video depicting President Joe Biden performing his dance. “[It] was really funny but at the same time, there was someone who paid someone to do the dance for them,” he said. “I definitely was not contacted for that.”